My Papa

A rememberence from Ken's first granddaughter, Cassandra, on the year anniversary of his passing.I’m Cassandra. I am Ken’s oldest granddaughter. I had the privilege of growing up right down the street from my grandparents – from my Papa. He came to all of my soccer games from the time I was seven to the time I was in college. He came to all of mine and my siblings school events throughout the years. He helped me with science projects in elementary school; and I even interviewed him and made him the subject of multiple college papers I wrote. He and my grandma hosted my 16th birthday dinner and college graduation party at their house. When my siblings and I were kids in the summer time, they would babysit and play with us outside. Papa would let us help him build a “tree house” in the backyard (that was really just three 2 x 4’s nailed to the tree). I was able to go to so many amazing places with him. I got to explore Spain with my grandparents and family when they came to visit me and to celebrate my grandparents 50th wedding anniversary. I got travel to the Philippines and see where my grandparents met and fell in love. We went on family vacations to Hawaii and had the great “Calhoun Convergence” in Alaska. But just having the luxury of being able to come over on a Sunday night for dinner and watch a baseball or basketball game all together – I just feel so fortunate to have had those moments. And yet, it still hurts so much knowing that I can’t just stop by their house and see him now. Or knowing that he won’t be with us physically during the holidays or special events. I have had so many wonderful experiences with my Papa but it still feels like we didn’t have enough time… What brings me comfort is something that I recently heard. It’s that “every kind of grief that exists starts with loving someone. So grief is really a signal that we loved or were loved greatly.” My Papa didn’t say the words “I love you” often, but for me, I realized he didn’t need to because he showed it through his actions. He was such a sweet and kind person and I have memories with him that I will cherish the rest of my life. I loved him greatly, and I know that he loved us all greatly too.

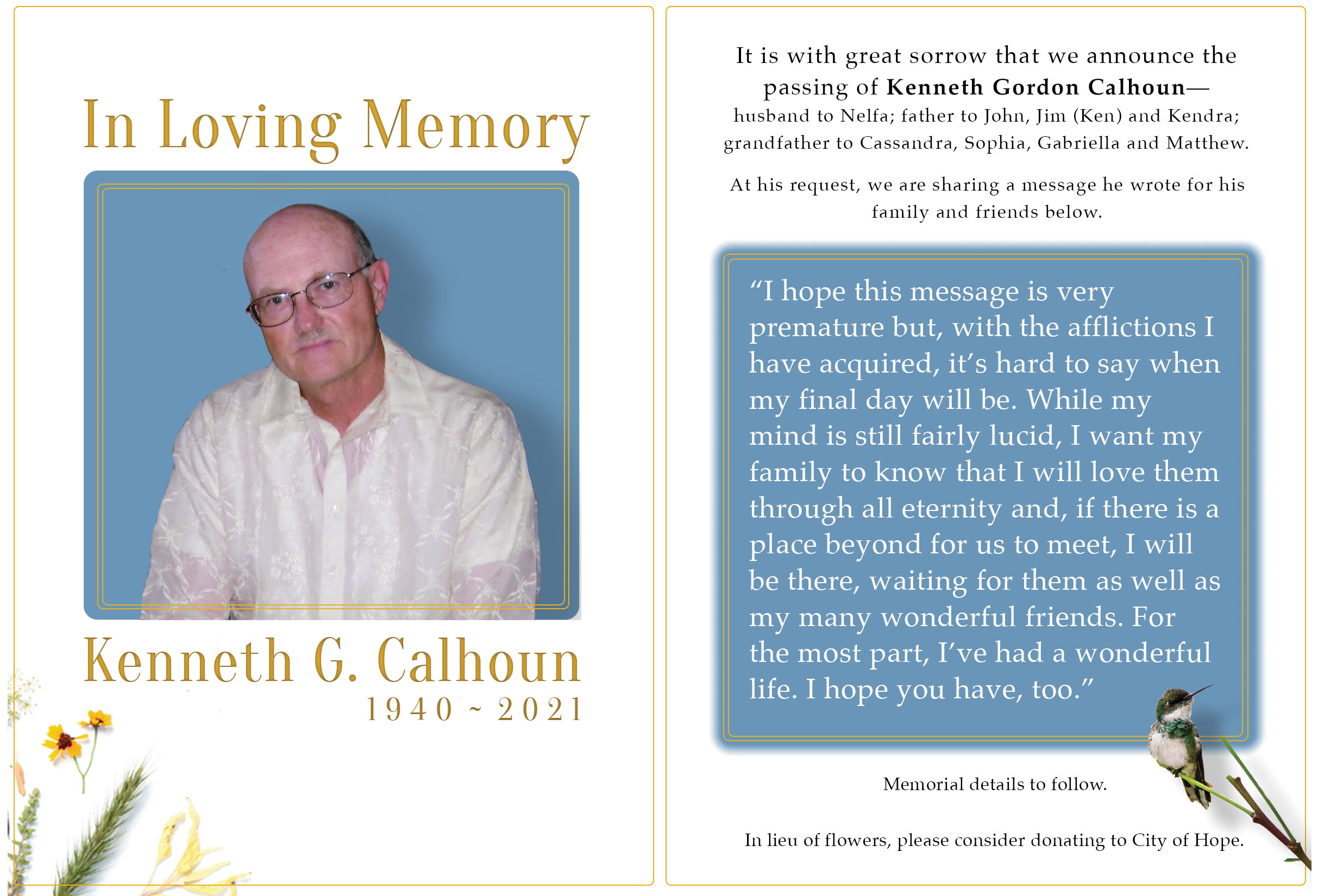

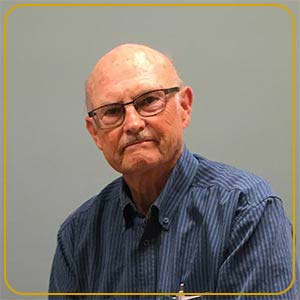

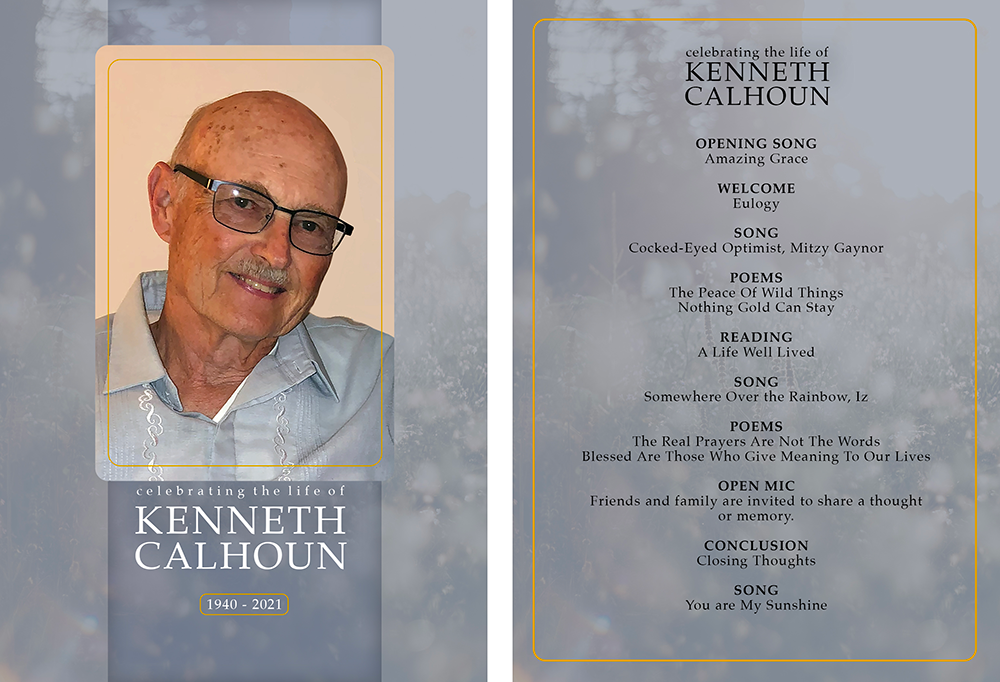

Obituary

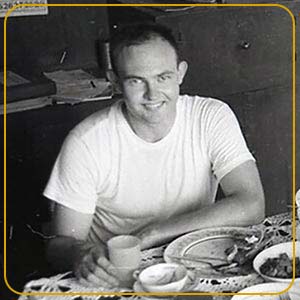

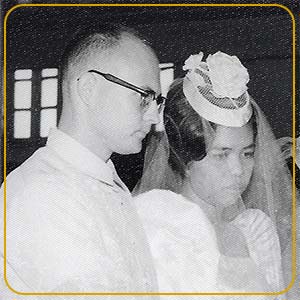

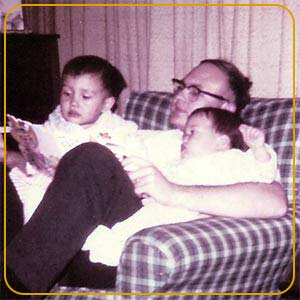

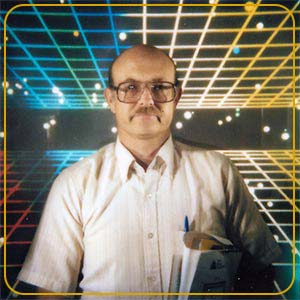

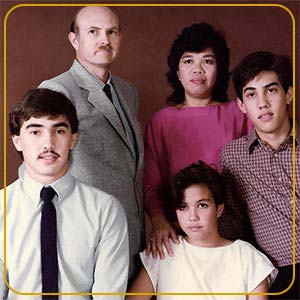

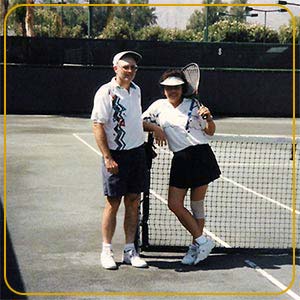

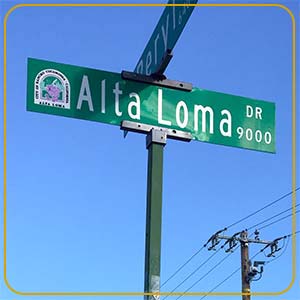

Kenneth Gordon Calhoun passed away on August 26th, 2021, in the loving presence of family, at San Antonio Hospital, where he was born eight decades earlier on December 5, 1940. A lifetime resident of California, Kenneth lived in Anaheim and Sacramento briefly, as a child, before the family resettled in Upland. He and his older brother, Gerald, were raised in a house on Euclid Avenue by their parents Clarence, a Chaffey educator, and Margaret, a former nurse. Kenneth earned a degree in Biology at the University of California, Riverside, before joining Kennedy’s newly formed Peace Corps. He soon found himself teaching science in the Philippines. There he met his beloved wife, Nelfa, who was teaching at the same institution. He married her in Bacolod City in 1964 and completed a Masters degree in Zoology at the University of the Philippines soon after. Upon returning to the U.S. with his wife and the first of his three children, he began his 35-year career as a professor of Biology, Physiology and Anatomy at Chaffey College. The teaching lifestyle allowed him opportunities to pursue his passions and interests, which included both playing and watching tennis as well as performing and appreciating music. A trombone player since his high school days, he enjoyed playing in Dixieland bands well into his 70s. Another lifelong interest was seeing the world. He visited many regions of the globe including Asia, Central America and Europe, where he explored Spain, Italy, Austria and France, as well as the United Kingdom, where he has family origins. He visited nearly every state in the U.S. and developed a special connection with Hawaii, particularly the Big Island, where he would spend several weeks each year in Waikoloa, near Kona. When home, he enjoyed being with his family, grilling salmon or steaks for the many gatherings and mixing a cocktail he invented called “Pliers,” which was a variation of a Screwdriver that he made with tangelos grown in his backyard. Throughout the year, he attended sporting events of his grandchildren, cheering on their efforts in soccer and golf. Kenneth was also an avid outdoorsman and naturalist. His favorite activities included biking, hiking and birding. He was never far from a field guide and could identify all the plants and animals of the area and beyond. For Kenneth, the natural world was an unending source of intellectual curiosity and inspiration. He was forever in awe at its beauty and complexity in any setting, delighting in the backyard activities of birds or the bloom of flowers in the parkway trees. Kenneth is survived by his wife, Nelfa Calhoun, his children, John (wife Natalie), Jim and Kendra, and his grandchildren Cassandra, Sophia, Gabriella and Matthew. He was dearly loved by his family and friends who will carry his memory into eternity. Donations to cancer research at City of Hope in his name would be greatly appreciated by the family.

Video

Eulogy

Somehow, very early in our lives, we started calling him “father”. We called our mother “mother”. Most kids called their parents mom and dad. Later, when we realized this was odd, and even felt a bit self-conscious about it, we asked him, Why did you want us to call you father? He said, “You guys started doing that on your own. We didn’t ask you to do that.” This seems likely, though I have no idea why my brother and I, as preschoolers, would insist on that formality. When our sister came along, six years late to the party, she didn’t get the memo and called him “daddy”. She was an extremely thirsty child and would often call out “dad-dy” at all hours of the night, then ask for a drink of water, which he always brought her despite her informal ways. She eventually switched to “father” though I’m not sure when. There were other odd formalities that we practiced in those early days. At night, when heading off to bed, we would kiss our mother on the cheek and say, “Goodnight, mother.” Then we would shake his hand and say, “Goodnight, father.” Sometimes, with this ritual out of the way, we would howl and jump on his back and he would carry us to our room. Sometimes we would lie on the ground and hold onto his ankles, and he would slog down the hallway, dragging us. I guess there was something about his look and manner that invited both responses—the formal and the playful. On the surface, he appeared reserved and buttoned-down, especially when compared to his Life Science colleagues, who were bearded and sandaled, who wore jeans in the classroom, while he wore slacks and shiny shoes, a pocket protector and glasses. Back then, he had the accessories of mid-Century man: a pocket comb, handkerchiefs, a shoeshine box, an assortment of pipes and tins of tobacco. He was, generally, calm and reasoned, with a kind of emotional economy that was even-keeled and analytical. He was a man of science, after all. He looked like someone called “father” by his kids at home. But, at home, he was fun and adventurous, truth be told. He’d take us on long walks through the brush—the undeveloped terrain behind our house that we called the Field. We would explore. He showed us where rabbits had slept in the grass, coyote dens, snake skins and puddles trembling with tadpoles. From him, we learned the names of raptors and songbirds, fence swifts and alligator lizards, wasps and peach beetles. He brought home a microscope from the college and we observed the spiked legs of flies and the brittle stalks of human hair, creatures in every drop of water. He brought me snakes and, to feed them, live mice in paper lunch sacks. Once, during our explorations, we spotted a treehouse high in the branches of an old oak and he climbed up and sat in it, shouting down a description of what he could see at those heights. When they put in the new power station on Campus and Baseline, he had us wait as he scaled the wall, dropped down the other side, very blatantly trespassing. Through the concrete slats, we watched as he examined the bizarre electrical equipment. I was certain he would be shocked, as the many warning signs suggested, but he managed to avoid all live wires. He could also be fiercely protective and downright lionhearted. I’ll never forget him charging through the sage at some bullies that were throwing rocks at me and my friends. He chased them halfway home, launching a small boulder after them as a parting shot. I remember this same energy sometimes emerged when he was driving. Many useful words were learned by those of us in the back seat who were paying attention—words that are used in similar contexts to this day, all over Boston, and probably Alaska, if not right here in the Inland Empire. He found ways to channel this lively aspect of himself into healthier outlets, like tennis, for example. Only recently he described himself to me as “pretty competitive” and, yes, I suddenly saw that he was, though he had done a good job of hiding it. I understand that this competitiveness was proven out by numerous victories on the tennis courts. This winning spirit was also there when he coached our soccer team or when he stood among the other parents and grandparents on the sideline of the field, or golf course, shouting his support. His tireless boosterism on our behalf wasn’t limited to sports. He patiently endured punk band rehearsals in his garage or living room and, very recently, asked Kendra to sing him a country song, commenting at the end that he preferred Kendra’s voice over that of Lucinda Williams—which is high praise. And he often asked about my progress on various writing projects and commiserated with me about hurdles I had come up against, always leaving me with the encouragement to keep going, to not give up. What we’re talking about is heart. The thing we have to recognize about this seemingly mild-mannered professor of biology, physiology and anatomy is that he was also a hopeless romantic. This was a man who finished college and joined a new idealistic organization called the Peace Corps. He traveled to the other side of the world and met a beautiful woman there. He courted this woman with secret messages in magazines, good American manners and at least one song he wrote in her honor. She brought Technicolor to a life that might have been otherwise destined for Leave To Beaver black-and-white. With her, he secured for himself a comfortable place outside of the ordinary and typical. His journey was on the road less traveled, because of her—and that made all the difference, as a poet once said. As you all know, they were inseparable—a single entity that always presented a unified front, which made it especially difficult to get away with adolescent shenanigans and teenage schemes. You couldn’t go over anyone’s head because it was the same head. They were always playing doubles on and off the court, and while this was a challenge for certain aspiring troublemakers, their relationship provided us with a model for commitment and unwavering loyalty. With her, he showed us how to share a life, how to play the long game of love. In fact, there were many things he taught us by the example he set, the choices he made and the disposition he passed on to us. Really, he gave a lifelong tutorial on how to be a grownup, to be decent and accountable, to always follow through. It’s hard to know how much you’ve been shaped, how much you’ve absorbed, until a particular situation draws it out of you. That situation, the one he prepared us for, is this moment right now, and the months that led up to it. Believe me when I tell you we fought hard to keep him, just as he fought hard to stay. I knew he was proud of how we came together and that he could see, in our response to his predicament, not only how much we loved him but also that we are a family who won’t shy away from hardship. In some ways, it was not unlike when we learned that he had taught one of the nurses looking after him at the hospital. She had gone through the nursing program at Chaffey and, now, here she was, checking his vitals around the clock. He had taught us too. Not so much to look after him, since he wasn’t one to put his own needs first, but how to look after each other. As tough as things got, no one in this family flinched, no one ran away, though it was certainly the hardest thing we have ever faced. Instead, he brought us together and made each one of us stronger in our effort to be all that the moment asked of us. His own optimism and hope set the tone. He took solace and strength from small comforts—a cold cream soda, freshly made salmon croquettes, hummingbirds at the window feeders and an oriole in the bird bath. Tennis on the TV. So much tennis on the TV. And did you know he loved musicals? In the hospital and at home, we watched Brigadoon, the King and I, Carousel, The Flower Drum Song and South Pacific. I’ve never seen anyone so transported as I did watching him watch a musical in a hospital bed. It was almost as though he was willing himself into those fantastic worlds where the backgrounds are perfectly painted landscapes and people just break out into song. Once we started South Pacific, but for reasons I can’t recall, we didn’t finish it. Maybe he had to be wheeled off for some tests, or maybe visiting hours were over. But the next day, when I returned, he said, “I remember one of the songs from South Pacific that you should look up.” “Oh, yeah?” I said. He told me that the song was called Cockeyed Optimist and that he’s always identified with it. He seemed to want me to write it down, so I tapped the title into the notes on my phone. Later, only a week ago in fact, I was deleting old notes and saw it. I looked up the lyrics. It ends with these lines: I'm stuck like a dope | With a thing called hope | And I can't get it out of my heart! | Not this heart... His hope went beyond himself, or even us—his friends and family. If you listen to the song, which we’re about to do, you’ll see that it’s song about hope for the world in general. It was his hope that this place, and our time here, can provide for everyone the happiness he enjoyed. He said it himself, in his final message to all of us: “I’ve had a wonderful life,” he wrote. “I hope you have, too.”

Cockeyed Optimist

Performed by Mitzi Gaynor

The Peace of Wild Things by Wendell Barry

Read by Cassandra Calhoun When despair for the world grows in me and I wake in the night at the least sound in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be, I go and lie down where the wood drake rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

Nothing Gold Can Stay by Robert Frost

Read by Matthew Calhoun Nature’s first green is gold, Her hardest hue to hold. Her early leaf’s a flower; But only so an hour. Then leaf subsides to leaf. So Eden sank to grief, So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.

The Real Prayers Are Not The Words, But The Attention That Goes Before by Mary Oliver

Read by Sophie Calhoun The little hawk leaned sideways and, tilted, rode the wind. Its eye at this distance looked like green glass; its feet were the color of butter. Speed, obviously, was joy. But then, so was the sudden, slow circle it carved into the slightly silvery air, and the squaring of its shoulders, and the pulling into itself the sharp-edged wings, and the falling into the grass where it tussled a moment, like a bundle of brown leaves, and then, again, lifted itself into the air, that butter-color clenched in order to hold a small, still body, and it flew off as my mind sang out oh all that loose, blue rink of sky, where does it go to, and why?

Blessed Are Those Who Give Meaning To Our Lives A Jewish Prayer

Read by Gabriella Calhoun Blessed are those who give meaning to our lives; Holy and precious is the example they leave behind. We pray: May our sorrows diminish as we recall their strength. May their wisdom protect us and help us to live. Let our grief be transformed into tenderness for those who are still with us.

Somewhere Over the Rainbow

Performed by Iz

Interment Address

On April 22, 2022, Ken's ashes were interred at Bellevue Cemetery in Ontario, California. A small gathering of family and friends were present for a simple ceremony at the site of his final resting place.

We miss him. We know he’s no longer physically with us, but the fact of his absence is a bit fuzzy. Sometimes, after all we went through this summer, we still forget he’s gone. Not with the full focus of our minds but along the soft edges. How else to explain those micro-moments when we operate as though he is just a phone call or message away? Or when we see an interesting bird or animal and we think, take a picture and send it to him—realizing even before the thought is complete that we can’t. When we are confronted with a tough decision and we think, I should call and get his take, before again—that terrible realization. When we see a movie or book or show or hear a song or learn something new about mosquitoes or trees or icy rocks in outer space and we think, I should share this with him, he’d find it interesting, almost at the exact same time that we understand—we understand. Or do we? Maybe that’s the wrong word. I’m not sure that we understand. Understanding involves processing and it’s been difficult to process. A better word might be know—we know, though we know only a little, really. Because most of what has happened and is happening is a mystery and I mean that in the grand philosophical sense. Mystery with a capital M. What we know—maybe all we know in the face of this mystery—is that we miss him dearly and that he is no longer physically with us. It’s my hope—not my understanding, and I certainly don’t presume to know—that the physical part of life is just a sliver of existence. A blip against the backdrop of eternity. And that eventually, as he himself said in his final message to family and friends, we will be united, in that shared state of consciousness that is not wedded to matter. And that then, together, we will have the greatest of understandings, and the access to all knowledge, and yet we will still look in delight and wonder at the astonishing charms of the earthly realm—this place, those birds, those trees, those icy rocks in space. There is another thing we know. We knew it all along but his leaving, his departure, surfaced our acknowledgement that we are all moving toward that other state—towards all that comes after, towards him. For a long time, this didn’t seem to be the case. Even though we grew up, even though kids came along and they, grew older, it seemed like we had created a bubble of timelessness. Maybe this was more profoundly felt by Kendra and I, since we moved away a long time ago. Whenever we came home, it was like going back in time to a smoggy Shangri-La, where 80s music was always on the radio and people still ate donuts and Vince’s spaghetti, where high school classmates worked in grocery stores and those mountains remained in place against the sky. The house was the same. We returned to our childhood bedrooms and family roles. And he was there, and our mother, living in the wheel of their satisfying routine—playing tennis, watching the news and Jeopardy, making meals, going for walks, hosting family. Immersed in the tradition of it all, I felt ageless when I visited, young, preserved. It seemed like it would go on forever. For me at least, the spell was broken on August 26th. I suspect we have all been made more aware of the ticking clock. There are relentlessly cruel configurations in this life, like cancer, but maybe the most sinister thing of all is time. Its indifference to our catastrophes is a terrible thing to endure. How it marches on. Carrying us away from our last moments with him like a current, distorting and fading memories, urging us to forget. We are in a fight with time and the distance it wants to impose between us and the man who is our father, and husband, and grandfather and friend. The only way I know to fight it—other than living fully in every moment—is to be together as much as possible. When we are together, we make a shape for which he is a foundational element. It’s a shape that invites his presence and reinvigorates our memories and the feeling of closeness. And why wouldn’t it? Yes, he lives on in our thoughts and memories and dreams—that unending life of the mind—but also in a much more concrete way for family, where he persists in our cells, in our blood, in our faces and expressions and movements. And he’s visible in friends too—in the imprint he left on you through all your interactions and in the smile his memory brings to your faces. He is present in the collective us. Which brings me to the third thing we know. Something that we knew all along and that, again, was surfaced by his passing: we love him. He loves us. We love each other. A binding force. I noted last summer, when we were all together, that we aren’t a family that says that word much—love—but we show it. We demonstrated it with clarity and intensity as we all fought to keep him here, just as we are saying it now, by coming together to see this aspect of him, these ashes, safely and lovingly placed in the spot he chose, in this valley where he grew up. We leave these ashes here with love, but the truth is his real resting place, as they call it, is in our hearts and minds. May he rest here in peace, but may he be lively, active and vital in our memories and dreams.